Building a blue economy for a brighter future

Why collaborative action on the high seas and close to shore

matters for the whole planet

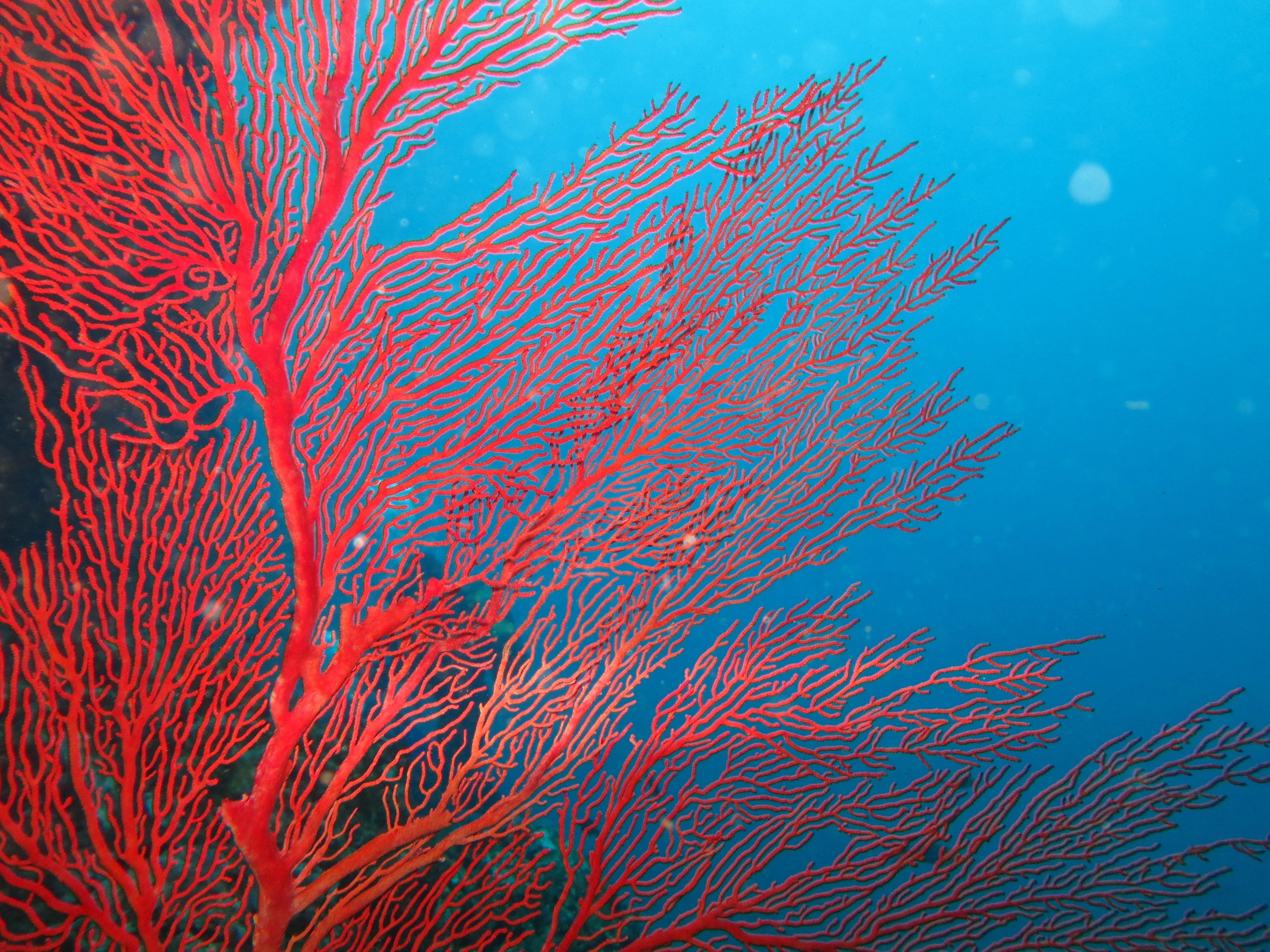

The global ocean is a critical resource, nurturing fishes, corals, marine mammals, deep-sea vent communities, and so much more—providing a home, refuge, and sustenance to countless weird and wonderful species. For humans, it also supplies a major source of food—4.3 billion people rely on the ocean for 15 percent of their protein— as well as jobs, from the fishing and tourism industries to the energy and transportation sectors. These can be pieces of a sustainable Blue Economy, where vibrant ocean and coastal areas foster economic growth and sustainable livelihoods.

The ocean also plays a critical role in regulating Earth’s climate by storing carbon in its depths for long periods of time, known as a carbon sink, and sequestering carbon in the wetlands, seagrasses, and mangroves along its shores; these also buffer the effects storms have on coastal ecosystems, infrastructure, and communities.

A healthy ocean is essential to a healthy planet. But today, many fish stocks are fished at capacity, overexploited or depleted, illegal and unregulated fishing is happening on the high seas, and pollution is commonplace, including plastics, which has been found in the ocean’s deepest trenches.

Given these challenges we must turn the tide towards a more sustainable future for our ocean and protect 30 percent of this global resource by 2030, fully addressing pollution, and improving planning and cooperation between countries. Here’s how:

Manage the ocean as a shared resource

The world’s ocean is divided up into Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) that are coastal areas hugging continents which stretch from estuaries and river basins near shorelines out towards the continental shelf and major ocean currents. The LMEs consist of economic zones exclusive to each country, and hold near coastal zones where most of the world’s fish catch is harvested. LMEs harbor transboundary fish stocks and share issues around pollution, the effects of climate change, and implementation of policy frameworks. All demand collaboration across political borders to cooperatively manage these important shared resources.

One approach that can help is a relatively new process called marine spatial planning, begun in 2006, which simultaneously considers ecological, economic, social and cultural objectives when developing marine plans in order to safeguard long-term ecosystem health as well as the well-being of people in these areas.

One of the ocean’s most productive ecosystems is the Benguela Current LME. It provides some $267 Billion in services a year—including fishing, transportation, oil gas, minerals, and tourism, among others—and stretches across Angola and Namibia to cover the western tip of South Africa.

To protect this shared resource, the GEF helped the three countries take joint steps to boost marine sustainability and protect the ecosystem together.

Promote sustainable fisheries

Marine fisheries employ more than 60 million people worldwide, as fishers and in postharvest jobs. Some 85 percent of these are small-scale fishers and workers that operate primarily in the coastal waters of developing countries, with women representing about half of workers, especially in the postharvest sector. Coastal fisheries contribute nearly 85 percent of the approximately 80 million tonnes per year produced by marine capture fisheries. But today, many fish stocks are fished at capacity, overexploited, or depleted, threatening many of these livelihoods and leaving no room to expand fishing operations.

One contributing factor to stock depletion is the way fishery management practices have been handled in the past: looking at the health of just one fish species at a time. This “single-species management” approach had blinders to the bigger picture of factors that can contribute to healthy fish stocks; things like predators, habitat, and water temperatures. Neglecting these elements can result in incorrect and unsustainable catch estimates, with too many fish being harvested.

Today, scientists use ecosystem-based fisheries management. As part of this holistic approach, managers look at where a fish lives, what it interacts with, and what else is happening in its environment that could affect fish stock numbers. They sometimes even consider the number of prey species, like forage fish, that are needed to keep populations of larger predator fish healthy to ensure that not too many forage fish are harvested.

Ecosystem-based fisheries management helps to keep fisheries sustainable—which in turn helps keep the ocean healthy, because all of these pieces are interconnected.

Protect coastal ecosystems

More than a third of the world’s population lives within 60 miles of the coast or estuaries, which are a major source of food and raw materials. And approximately 50 million people move into these coastal zones each year, looking to benefit from ready access to trade and transport. Coastal wetlands are home to some of the planet’s richest biodiversity. Salt marshes, seagrass beds, and the shallow waters where mangroves are rooted provide refuge for wildlife and nurseries for juvenile fish, including some species that are commercially important like groupers and snappers.

These habitats can help vulnerable coastal communities adapt to a changing climate by helping to stabilize shorelines, protect from erosion, and serve as a buffer from walloping storms. Coastal wetlands sequester large amounts of carbon in the soil, helping to mitigate the effects of climate change. As one scientist put it: “Mangroves are the rock stars of carbon sequestration because they stockpile carbon at a rate 10 times higher than tropical rainforests.” However, a lack of proper valuation of mangroves and their associated coastal ecosystems, and the fact that mangroves often occupy high value coastal zones that may present countries with opportunities for short-term economic gains, means they are often not considered to be as important as the massive rainforests. But they should be. Plus, their appearance is quite striking, with expansive and twisted raised root systems resembling something out of a Grimm’s Fairy Tale.

Despite all of the benefits coastal habitats offer, they are among the most threatened ecosystems in the world, particularly vulnerable to overexploitation because they include large areas that have been traditionally perceived as a public “commons,” such as beaches. These unique and multifaceted resources need safeguarding.

Rethink pollution

Plastics touch our modern lives every day, as water bottles, hand sanitizer containers, plastic wrap, food packaging, convenience store cutlery, sandwich and grocery bags, and much more. And a surprising quantity of it ends up in the ocean.

Today, 11-13 million tons of plastic reaches our oceans every year, the equivalent of a garbage truck full of plastic dumped into the ocean each minute. Without interventions, scientists say that amount will quadruple by 2050, to four full garbage trucks dumped every minute. And some kinds of plastic can take close to 500 years to break down.

Once in the ocean, plastic can be ingested by animals, and can also entangle them. Both can kill. The problem is so ubiquitous that a plastic bag has been photographed at the bottom of the Mariana Trench, the deepest point in the ocean. And in 2012, Indonesian surfer Dede Suryana was photographed riding a literal wave of plastic trash off a remote island in Java’s once pristine waters.

But while plastics are a very visible problem, other pollutants are difficult to see. For example, dissolved inorganic nitrogen is prevalent in coastal areas from streams of agricultural runoff that include fertilizer and manure, and it also comes from sewer discharge. In large enough amounts, nitrogen can cause an increase in phytoplankton as well as algal blooms that can damage or kill plant, fish, and shellfish populations.

Phosphorus is another nutrient that can likewise wreak havoc. It’s estimated that half of all nitrogen and phosphorus pollution in the ocean begins with human activities. Yet another unseen threat comes from persistent organic pollutants (POPs), industrial chemicals or byproducts that can have devastating effects on human health.

There are many potential solutions. For plastics, it starts with the 5 Rs: rethink, redesign, reduce, reuse, and recycle. But it will also require stopping the massive flow of plastic by eliminating ‘single use’ plastics—such as plastic straws— and shifting to a circular economy approach which extends the life of plastics and recycles discarded materials back into the production phase.

Agricultural runoff can be tamed through smart farming practices and by improving manure and nutrient management, as well as through widespread education campaigns. Sewer runoff requires concerted water treatment efforts. And POPs can be reduced through sound chemical and waste management, especially in countries undergoing economic transitions.

Prioritize the high seas

The high seas, areas 200 nautical miles or more from shore, are places where no country has jurisdiction. They make up 40 percent of the surface of our planet, comprising 64 percent of the surface of the ocean and nearly 95 percent of its volume. The ocean here, as in many other areas, plays a critical role for Earth’s climate, storing carbon in its depths for long periods of time through a process known as a carbon sink. The high seas are also a place where illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing is happening—carried out by unlicensed vessels, without permission from governing bodies or attention to conservation or management measures.

IUU fishing is estimated to account for some 25 percent of all fishing activity globally each year, representing up to 26 million tons of fish caught annually at a cost of $10 - $23 billion to the global economy. But the costs to conservation efforts are harder to calculate and can be devastating. One innovative program to combat this problem, called Eyes in the Sky, involves using satellites to track IUU boats, so they can be caught, fined, deterred, and stopped. Another important tool to curb IUU fishing is the adoption and implementation of the Port State Measurement Agreement, which prevents these vessels from using ports and landing their catches through a series of guidelines countries can apply to ships within their ports or seeking entry to them. This framework is one of the most effective tools deployed to help governments stop IUU fishing.

Other high seas activities include operations to explore seabeds for deep sea mining, oil and gas exploration, and hydropower generation, and transport, and all of these activities can damage marine ecosystems.

Recognizing the vital role the high seas play in climate regulation, a key international body passed a motion urging the United Nations to finalize a treaty to protect the high seas by early 2022.

If adopted, a high seas treaty would help protect biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction and allow for the establishment of marine protected areas.

Managing ocean resources is a global responsibility

The solution to a healthier ocean involves taking a big-picture approach, much in the way that ecosystem-based fisheries management addresses every individual element that could impact the numbers of fishes. Issues affecting the ocean are interrelated, and changes to one of them can throw another out of balance. A coordinated, cross-national effort will be needed to shore up the health of the ocean through sustainable fisheries practices, protected coastal ecosystems, a reduction in pollution, and efforts to reduce illegal and unmonitored activities on the high seas.

It’s time to embrace a wave of new ideas around the ocean. Our collective future depends on it.