How it all began

30th Anniversary of the Global Environment Facility

Environmental destruction is as old as civilization itself. Egyptian mummies have lungs blackened by the polluted air they breathed. Rome began building aqueducts for drinking water after dumping its sewage in the Tiber. Forests were felled to make ancient Greek ships and ink - from tree bark – for the bureaucrats of China's Tang dynasty. And Gilgamesh, the world's first known written story, warned against land degradation in Mesopotamia.

Most of the effects, throughout human history have been local. At times – and increasingly – they have spread regionally. Disregarding Gilgamesh's warning caused desertification which helped cause the collapse of Sumerian civilization, while – in our own time – nutrient pollution washing down rivers has produced dead zones in distant seas, and air pollution has fallen as acid rain hundreds of miles away.

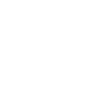

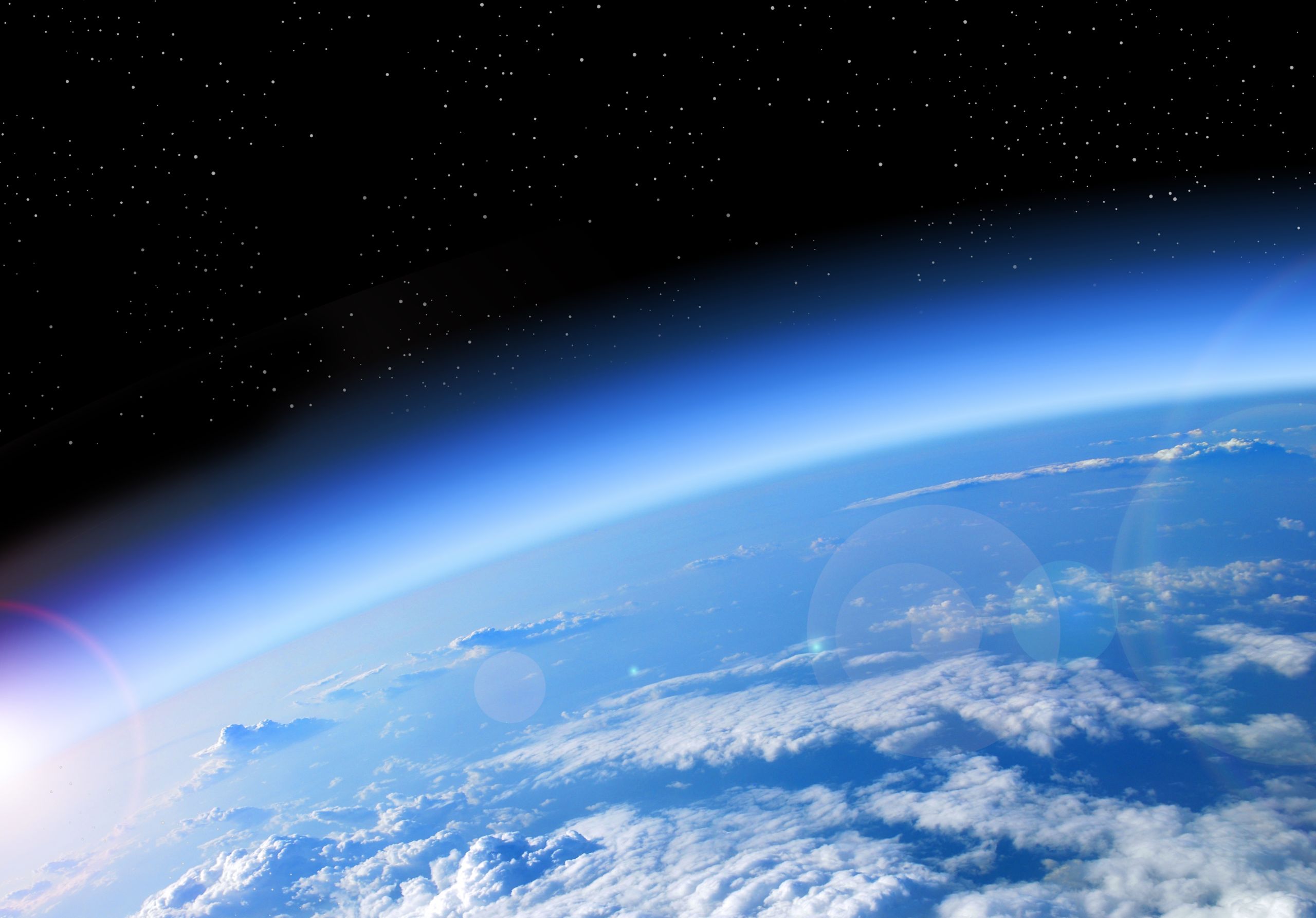

But it was not until the 1980s that environmental damage went global. Man-made chemicals were found to be eroding the protective ozone layer. The first, courageous, scientists began warning that climate change was taking place. And it started to become clear that the rate of loss of species was rivalling the great extinctions in the geological record.

Spurred by public concern, the international community was quick to respond. The successful Montreal Protocol, which has so far reduced some hundred ozone-depleting substances by a total of 98 per cent, was agreed in 1987 within four years of the discovery of the ozone hole over Antarctica. Negotiations on the UN’s Framework Convention on Climate Change, Convention of Biological Diversity, and Convention to Combat Desertification followed, and these were agreed in 1992. But the world also needed an international financial mechanism to tackle global environmental problems and help implement the new conventions.

In September 1989 France proposed, through its Finance Minister, that the World Bank be provided with additional resources to fund environmental projects, offering to support it with a contribution of 900 million French francs over a three year period. Its proposal, to the Bank's Development Committee, was quickly seconded by Germany. And little more than a year later - in November 1990 – after the Bank had developed the proposal, with extensive consultations and negotiations - 27 countries, including nine developing ones, agreed to set up a pilot Global Environment Facility (GEF), with about $1 billion for its first three years.

The money was to be spent in developing countries, and concentrated on four focal areas: climate change, biodiversity, ozone depletion and international waters. And the facility was to be managed by a collective of three well-established organizations: the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and the World Bank. - referred to as “implementing agencies”

It was a remarkable, as well as a rapid, development. For a start, it took place at a time of financial stringency: the $1 billion budget represented a considerable vote of confidence in the pilot GEF. Even more significantly, it was set up as a loosely structured, action-orientated organization which did not involve establishing a new bureaucracy - something very unusual, indeed innovative, for the international community.

It was also exceptional in that – being first proposed by a finance minister, and developed by the World Bank – the new initiative viewed global environmental issues from a primarily financial perspective and was thus designed to prioritize efficient decision-making and cost-effective operations.

The aim was to benefit the whole planet, by enabling developing countries to take actions that they could otherwise not afford, but it was equally important that this should not divert resources from their need to develop. So it was made an absolute requirement that the GEF's funds should be additional development assistance, not redirected from existing provision. Furthermore, they had also to be additional to activities that developing countries were already taking that made national economic sense. So the concept emerged of financing “incremental cost”, the extra expense incurred when activities also benefited the global environment, which would otherwise have been discouraged by standard economic analysis.

The pilot GEF started work on its three year, exploratory programme - an opportunity to test innovative approaches since funding projects to improve the global environment was something new. The World Bank acted as both trustee and administrator, and as the main interface with participating countries: UNDP developed most of the capacity building proposals: and UNEP concentrated on strategic planning and issues concerning science and technology. It was, in yet another innovation, a remarkable blend of UN and Bretton Woods institutions. The first tranche of projects was presented to the first meeting of the participants in May 1991, which also established the GEF's Small Grants Programme.

This was not much more than a year before the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development – the Earth Summit – met in Rio. Preparations for the summit – and negotiations on treaties – were well under way, and the fledgling pilot facility was soon involved. Developing countries were increasingly, and rightly, coming center stage and NGOs – who were given a more prominent role at the summit than ever before – were getting more and more engaged. Both were suspicious of the World Bank's dominance of the pilot facility.

In June 1991, developing countries proposed - in the Beijing Ministerial Declaration on Environment and Development- that a special Green Fund should be set up “to address problems which are not covered by specific international agreements, such as water pollution, coastal pollution affecting mangrove forest, shortages and degradation of fresh water resources, deforestation, soil loss, land degradation and desertification”. It should, they added, “be managed on the basis of equitable representation from developing and developed countries, and should ensure easy access for developing countries.”

They were concerned that the GEF might evolve into a substitute for such a fund and there was increasing concern among both participating countries and the implementing agencies that the pilot facility – though negotiated and agreed less than a year before – did not accord with the emerging political realities. At this point the facility got a new Chairman, who was to prove the key figure in its early history. Mohamed El-Ashry – who had been Vice President of the World Resources Institute when it had published a pioneering report calling for an International Environment Facility – was appointed Director of the World Bank's Environment Department in late May 1991 and was confirmed as GEF Chairman that November.

At his first Participants Meeting in December 1991 – which was also preceded by another innovation, a consultation with NGOs – Mr El-Ashry, as he recalls, warned that “this animal is not going to fly”. Developing countries, in particular, stressed the need for universal membership of the GEF and democratic decision making, and the donors agreed that a paper giving options of future development should be drawn up.

The paper, duly presented to the next meeting in the following February, gave three alternatives: continuing with the status quo; creating an independent institution; and having a modified, and incrementally evolving, GEF. It was little surprise that the last of these was chosen. Importantly, the meeting also reconfirmed that the GEF's basic mission was “to provide concessionary and additional funding of the incremental costs for achieving global environmental benefits” and, for the present, would be limited to its four focal areas.

How the GEF would be modified, however, had yet to be decided and the Earth Summit was coming closer. In the final weeks before it opened, the negotiators of the climate and biodiversity conventions – due to be adopted in Rio in June– agreed that it should be designated as the interim operator of their agreements' financial mechanisms, on the basis that it would be restructured and its membership made universal. Meanwhile a Participants Meeting in April had begun considering a blue print for restructuring, called The Pilot Phase and Beyond, and had agreed that “land degradation issues, primarily desertification and deforestation” would also be eligible for funding.

Developing countries – wanting funding for addressing their national environmental problems – had still, however, not formally abandoned their wish for a Green Fund, but developed countries would not consider it. Some solution had to be found if financing the implementation of the conventions – and of Agenda 21, the main program to be adopted at Rio – was to take place. Mr El-Ashry therefore persuaded the President of the World Bank to propose an 'Earth Increment' of additional money to address national environmental problems for the International Development Association (IDA), the part of the bank that assists the poorest countries. Leaders of industrialized countries promised in speeches to support the Increment at Rio, and the impasse was resolved, enabling agreement.

But once the Earth Summit was over, the donors failed to provide any more money for IDA, thus fueling a sense of betrayal among developing nations. Implementation of Agenda 21 suffered. The GEF was left as the only potential source of new funding, and thus its restructuring – negotiations on which began immediately – became a crucial test of political will.

Eighteen months of intensive talks followed in Abidjan, Rome, Beijing, Washington DC and Paris. They ranged over a wide variety of issues, but developing countries emphasized such principles as universal membership and democratic decision making, while industrialized ones stressed that these needed to be balanced with efficient process for decision-making and cost-effective operations. But gradually the differences narrowed, and in December 1993, the participants assembled again in Cartagena to reach final agreement on four outstanding issues – how often an Assembly of all participating nations should meet, how many countries should sit on the governing council, how it should make decisions, and who should chair it.

The meeting turned out to be a disaster. The atmosphere was edgy from the beginning, but progress was still made until some key delegations were reined back by their governments saying that they had negotiated beyond their instructions, causing collapse. Mr El-Ashry took the view that a collapse would be better than a fudged compromise that left both sides unhappy and unwilling to implement it. So he closed the meeting, changed his flight, and left – despite entreaties - without a setting a date for a future one.

Not just the future of the GEF – which could have become stillborn – but the implementation of the Rio conventions was now at risk, but El-Ashry was determined not to hold another, and make-or-break, meeting until he was sure there was a chance of a final agreement. Indications of that came in February 1994, at a separate meeting of environment ministers at Agra, India. After being briefed on what had happened in Cartagena, they called for a “speedy and successful conclusion” to the negotiations.

Taking his opportunity, El-Ashry brought together a group of participants who were attending a UN meeting in New York over dinner a few days later, and got their agreement to a full meeting in Geneva less than two weeks beyond that. Seventy-three participating countries turned up, realizing that thus was their last chance for an accord. Innovating again, it was decided, that the bargaining would take place between only three people – one representative each for the developing and OECD countries, with the Mr El-Ashry as moderator.

Even so, and despite a much more constructive atmosphere, little progress was made for a day and a half. As time began to run out, the two representatives finally asked El-Ashry to draw up his own proposals for agreement on the outstanding issues. He presented a two page paper to the whole meeting. It proposed that the Assembly should meet once every three years and that the Council should be made up of 32 seats, 16 for developing countries, 14 for OECD ones and two for economies in transition.

Decisions, where consensus was not reached, were to be made by a double majority vote – the first with an equal vote for each country, the second weighted according to financial contributions needing a 60 per cent majority, a highly innovative combination of the UN and Bretton Woods institutions voting systems. And the Chair was to be split. The GEF would be managed by a CEO who is also the Chairman. However, participants would elect one of their number to preside over administrative matters for the duration of each meeting.

When this compromise was presented, the meeting exploded in applause. Agreement was reached, and the delegates proceeded to replenish the GEF's funds to the tune of some $2 billion for the next four years.

Since then, under El-Ashry and his successors - Leonard Good, Monique Barbut, Naoko Ishii and Carlos Manuel Rodriguez – the GEF's four-yearly replenishments (it is at present on its eighth) have grown to over $4 billion. The original three implementing agencies have increased to 18 including other UN agencies multilateral development banks and NGOs.

It now serves as the financial mechanism for the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants and the Minamata Convention on Mercury, as well as for the three treaties agreed in 1992 in Rio and focuses on six main areas – biodiversity, climate change, chemicals and waste, international waters, land degradation, and forests.

Over the last 30 years it has provided more than $21.5 billion in grants and mobilized an additional $117 billion in co-financing for more than 5,000 projects. And, through its Small Grants Programme, it has provided support to more than 25,000 civil society and community initiatives in 135 countries.

In June 2020 the GEF council elected Carlos Manuel Rodriguez, then Environment and Energy Minister of Costa Rica, as its fifth CEO and Chairperson. During three ministerial terms he had overseen the doubling in size of his country's forests, the conversion of its electrical sector to 100 per cent clean and renewable energy, and the consolidation of a National Park System that has positioned it as a prime ecotourism destination. He had already been involved in the GEF - as the representative of a recipient government, an academic and an NGO official - throughout its history.

Opening his first Council meeting, in December 2020, he paid tribute to the GEF's “three decades of practical, on-the-ground experience applying innovative solutions to environmental challenges of all kinds” and its “focus on tackling the underlying drivers of environmental degradation, not just their symptoms. And he added: “Our job is more important now than ever!”